©Bernard Boyer

Souvenir photos

Daniel Buren has always paid particular attention to the use of photography and the confusion or paradoxes it can trigger in art.

When he has completed a work, he photographs it. Since 1967, he has called these documents “souvenir photos,” meaning that these necessarily fragmentary images are not the work itself. Nor are they copies or equivalents of it in any way whatsoever: they are just reminders, tools.

Indeed photography irremediably eliminates crucial features of the work: it imposes a single viewpoint – chosen by the photographer –, flattens depth and makes it impossible to walk around the work. The spectator’s view is necessarily passive and “manipulated.”

Yet these souvenir photos have an essential status, because the works in situ are by nature ephemeral and, with a few rare exceptions, are doomed to disappear. The photos are all that is left. And the only possible retrospective of Daniel Buren’s art, in the traditional sense of the term, would be a printed collection of all these souvenir photos.

Why a book? Firstly because a work in situ cannot be moved and reinstalled, but also because these images, whose very name deliberately reminds us of holiday snapshots, can be printed in books, on postcards or posters, published on Internet, but certainly not exhibited in a museum or even commercialised. The danger then would be to see them as works of art, to frame them and hang them on the wall, to sell them as unique “traces” of the work, as many artists have done with ephemeral works, thereby perverting their original creations.

Daniel Buren categorically refuses to give photography this function. For him, nothing can replace the visual, plastic experience of an art work. The photograph, although it is necessary as proof, must be content with its role as a souvenir photo. It refreshes our memories, testifies, evokes and betrays all at once. It is an “unpretentious image.”

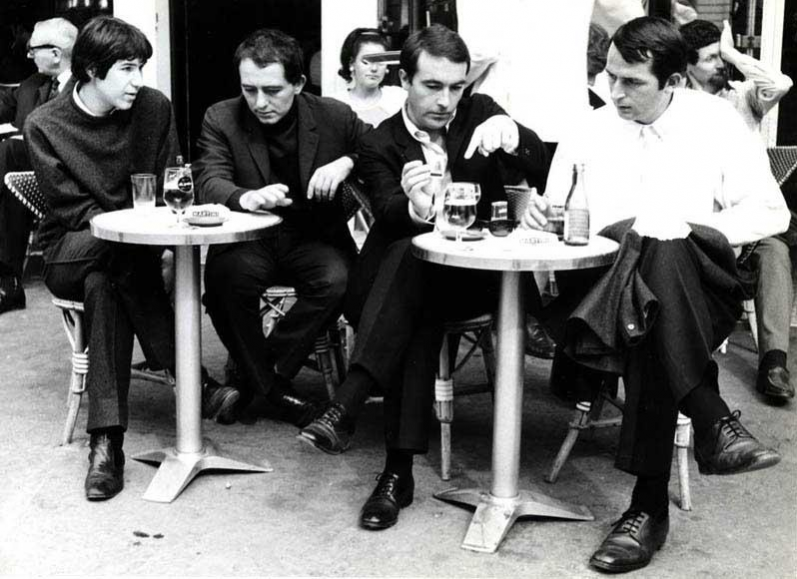

Photo-souvenir : « (de g. à d.) Olivier Mosset, Daniel Buren, Michel Parmentier et Niele Toroni à la terrasse d’un café » septembre 1967.

Photo-souvenir : « (de g. à d.) Olivier Mosset, Daniel Buren, Michel Parmentier et Niele Toroni à la terrasse d’un café » septembre 1967.